Squats and Myths

Dr. Mel C. Siff School of Mechanical Engineering University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa

My comments on squatting technique have drawn a mixed bag of agreement and upset, which is always the case with fundamental exercises which tend to be surrounded by years of superstitious application.

GENERAL COMMENTS

Rest assured that this type of analysis is not meant to belittle. Heaven knows how many times we are all challenged at lectures, conferences and lifting platform about the appropriateness of our technique. I thank those who have chosen not to be politically correct and kind to me over the years, otherwise I would have been happily contented with the same old myths forever.

Argumentation, analysis, refutation, rebuttal and counterproposal are all time-tested ways of research and teaching. Regrettably we often feel that if someone attacks ideas we believe in, then we are being personally attacked. Most of the time we did not even create the offending idea, yet we have used it so often that we become emotionally attached to it. In the case of religion, politics and sex, criticism invariably leads to such passionate encounters that even families become split up and nations go to war. Even science is not immune to this belief fervor – just try to argue about evolution and you will see what I mean.

In the world of fitness, a similar scene rules and it is inordinately easy to tread on toes. The one merit of the Internet is that everyone can attend (unlike some costly conferences and some forbidding lecturers) and become involved and for that we thank fellow list member, Pansy. She prodded all of us into a series of encounters from which we will all emerge enriched, if personality clashes do not cloud the content. So, those of us such as myself who have analyzed your comments in some depth still appreciate your willingness to become involved.

SOME SPECIFICS

That having been said, it is still essential to comment on one of the worst beliefs that one encounters at virtually every fitness convention and in every popular publication, namely:

“This exercise is for the average person or beginner and is not meant for athletes or experts"

While the sentiments are well founded, they often tend to insult the ‘average’ person – who on earth always wants to be just ‘average’? None of my clients wants to stay ‘average’ or ‘novice’ – that’s why they are visiting a professional – they want to move out of averages and progress to something far greater.

Of course, we start with carefully graded sequences of exercises, beginning with no added loading, and then progress cyclically to greater heights to achieve mutually agreed-upon goals, but we must never lose sight of the fact that any beginner HAS to be moving progressively onto significant resistance (or duration, degree of difficulty, range of movement etc.) – and this is where the problems begin.

Research has shown that skills developed with minimal loading do not necessarily transfer effectively and safely to situations with greater loading. Moreover, learning a skill using movements which are similar to, but not the same as the actual exercise being taught, causes the same sort of motor problem, because the controlling program being instilled into the central nervous system is different for every different variant or pattern of movement.

Thus learning of the half squat, power clean or machine bench press does not properly prepare the beginner for safety and efficiency with heavier loads. In fact, the well-meaning, but misguided advice to do certain ‘safe’ movements can actually lead to the dangerous situation in which the client may be MORE vulnerable to injury if he/she by chance is called upon to execute the banned form of that exercise.

ADAPTATION AND OVERDESIGN

Just as one overdesigns roads and buildings with a greater “Safety Factor" than 1 to withstand greater loads in earthquake zones such as San Francisco, so we should overdesign the body just in case it is sometimes called upon to do that dread activity that all the fitness authorities cautioned us against.

So we have to teach, modify or relearn the skill each time we are exposed to some noticeable change in its characteristics, such as degree of resistance, range, speed, duration and pattern. If one is likely to be exposed to fatigue with an exercise, then we have to ensure that the client knows the different skills of learning and coping under conditions of fatigue. It is highly misleading to believe that there is only one specific skill for a given exercise at a given time for every single person.

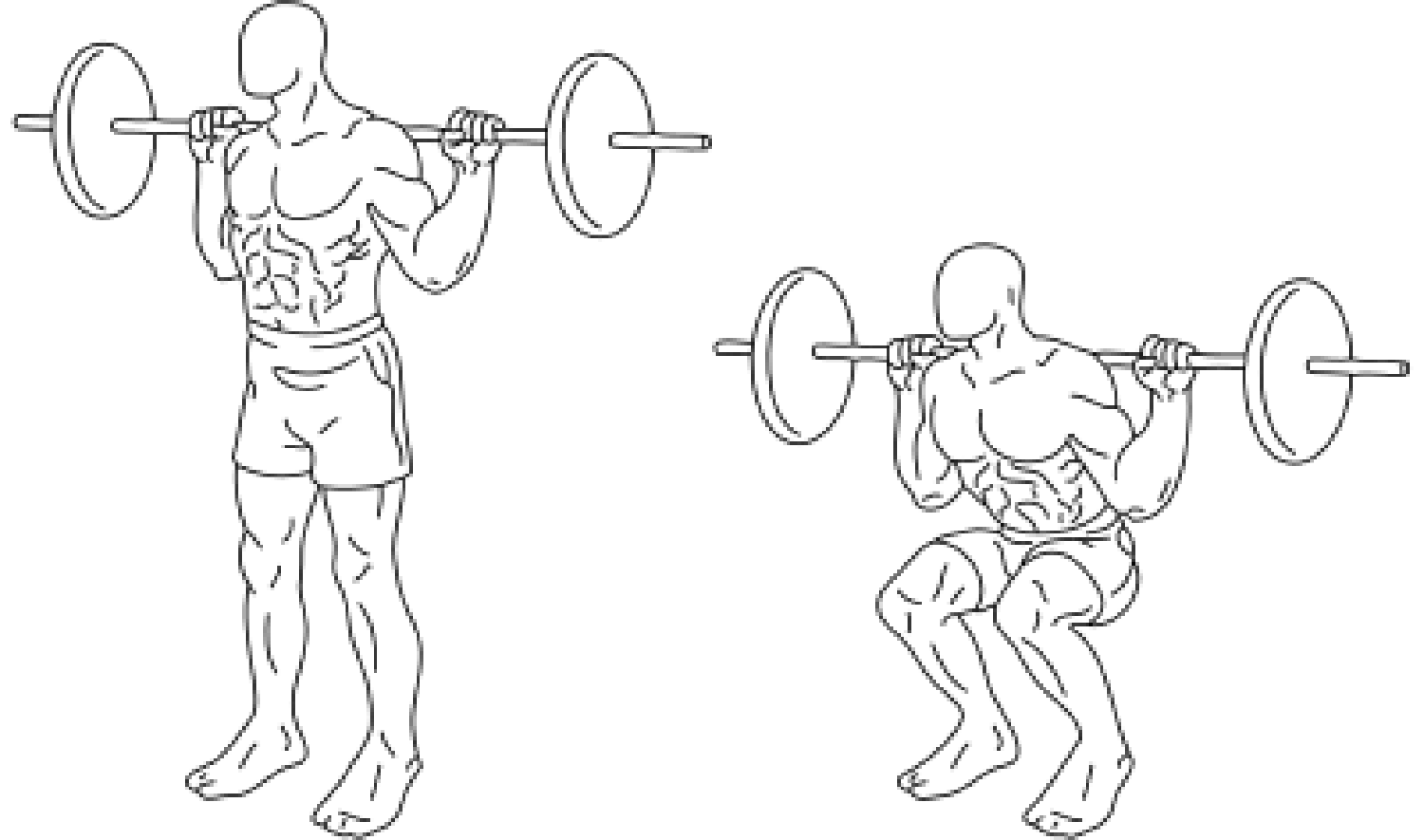

It is also misleading to lump all squats together. Even though they all involve knee, hip and spinal actions, the powerlifting and weightlifting or deep-knee bend squats differ very significantly in execution and distribution of forces through range of movement.

There tends to be an irrational fear associated with deeper-than-parallel squats, even though most of this is based on theoretical analysis and is usually contradicted by clinical studies which show that even more knee injuries occur in activities which do not flex the knee anywhere near parallel (such as running and jumping). Others show that partial squats can traumatize the knees even more than full squats!

Do the critics not appreciate that full squats executed under appropriate control throughout the movement actually produce adaptation (that is what all training is about, anyway!), enhanced strength, better stability and greater resistance to unexpected loading? That is what the principle of Gradual Progressive Overload is about, isn’t it?

THE REAL DANGERS

The sooner folk realize that safety of execution does not depend primarily on the exercise alone, but the technique with which it is executed. Thus, a full squat executed slowly over full range may produce smaller patellar tendon forces than a part-range squat done a bit more rapidly. As a matter of fact, the patellar tendon force is frequently much greater during step aerobics, running, jumping, kicking and swimming than during controlled full squats with a load even exceeding twice bodymass.

The dangers of a squat (even a part-range one) lie more in inward rotation of the knees, unequal thrusting with one leg, loss of stability with fatigue or poor concentration, unskilled use of ballistic action or the use of some object to raise the heels and increase the stress on the patella and its tendon.

Does this mean that we should then advise against all these activities? Of course not! If we presented a table of the stresses and strains acting on all the tissues of the body during apparently innocuous daily activities (including the pressure in smaller blood vessels subjected to the pumping pressure of the heart), we would never get out of bed.

Sorry, these arguments of great forces and stresses and so forth have to be looked at in context – the body grows, adapts and flourishes in response to an optimal level of regularly imposed stress. It is also misleading to talk about forces and tensions being large, because we should only do so in the context of knowing something about how big, strong and dense the tissues are upon which they are acting.

If the tendon has a large cross-sectional area and the connective tissue comprising it is strong and extensible, then we have far less to worry about than if the tendons were not like that. Remember that a knowledge of the STRESS (force averaged over the cross-sectional area of the tissue) and STRAIN (how much the tissues lengthen relative to their original length) is far more relevant than the force itself. Forget about forces being quoted out of context – we have to be far more specific than that before we can condemn some poor exercise to death.

SOME DISCUSSION OF DISAGREEMENTS

GENERAL

Like I said above, at no time did I suggest this was appropriate for actual training but was trying to create an idea of overall form. When did I ever say “significant weight" or bouncing or doing it fast? Remember my objective was to help in form, in bodily placement, not in an actual weight training program.

EVERYTHING is part of training and appropriate or inappropriate for training. My comments about overall form are answered by my analysis of how much the skills of execution vary all the time and that beginner methods may not necessarily be enough to ensure that efficiency and safety continue to reign. In terms of the two criteria applied to problem-solving situations, those initial drills may be NECESSARY, but they are not SUFFICIENT for learning squats which gradually increase in degree of difficulty (even if the difficulty is because one is growing older and weaker!)

If the next response is that the client is never going to add a load and remain at the same level and number of reps, I must say no more and go my way in peace. But if progressive increase in fitness is the aim, well, all the preceding commentary remains relevant.

When did I ever say significant weight? Again, I was trying to get across placement not an actual training routine.

Another little problem lurks in this comment. It is commonly believed that adding an external load is the only way to produce really significant loads on the joints and tissues. This myth has beset resistance training for decades and many coaches and doctors still believe that non-load bearing exercise has to be safer than load-bearing exercise.

If we wander back to Newton’s 2nd Law (Force F = Mass x Acceleration), we learn that the force may be increased either by adding load or by accelerating the action. In fact, since it is easier to move faster or accelerate more rapidly with a heavy load, many folk expose themselves to greater force under unloaded conditions! If one accelerates rapidly, the effective weight or load imposed on the body DOES become significant! This is always something we have to watch out for with beginners or those who believe in using light weights.

With this present myth of 90 degree angle, are you then suggesting that it is appropriate for a beginner to do a deep knee bend?

Do the persons suffer from any pre-existing knee problems or weakness? Do they ever squat in daily life to put on shoes or play with youngsters? Do they ever run, jump or kick without experiencing knee pain or disability? Is there any good medical reason which definitely indicates that slow, controlled full squats without major bouncing are dangerous for them? Do they always want to have a limited range of functional knee flexion for the rest of her life? Do they believe that the body was created or evolved NOT to be used in a controlled fashion (and sometimes for emergencies) over the full range of its capabilities? If the answer to all those questions is yes, then let them continue to treat themselves as if they are ready for the grave!

Also entirely relevant to the 90 degree story is the fact that more research is emerging which shows that this limited range squatting can actually place GREATER stress on the various structures of the knee joint than full range movement.

My old Bulgarian weightlifting coach used to try to convince me that I should even used a controlled bounce at the bottom of all of my squats in the clean and snatch to ensure that I did not damage my knees!! He and many of his colleagues did this for years with loads of as much as 240kg and after several decades of lifting they still had no obvious knee dysfunction.

I have not come across any research which supports his advice, but it would appear that he was recommending that one must involve the elastic structures of the joints to augment the ‘pure’ muscle contraction characteristic of slow controlled squats. Why rely just on muscles, when you can use stored elastic potential energy as well and spare the poor old muscle, seemed to be his view? I await information from others in this regard.

POSITION OF THE TORSO

Other contributors stressed the importance of squatting with the trunk vertical, which is another one of those horrible myths about squatting. To analyze this advice, let us return to the training chair that started all this discussion.

Sit erect with knees in front of you (or a bit to the side), shoulder width or so apart, hands folded across the chest, according to the advice we have just read. Without leaning forwards or shifting the feet further back and flexing the knees more, try to stand up without leaning forwards or bouncing!

You will find that this is impossible. To stand up, you either have to spread your legs very wide apart, like the Sumo squat position of the powerlifter, or move the feet backwards and lean forward. For most ‘average’ folk and serious lifters, the latter position quite naturally teaches you your individual degree of forward trunk lean for squatting and deadlifting. You HAVE to lean forward to squat or deadlift (now don’t quote some of those weird 19th century lifts with the load behind the ankles to prove this wrong!); that is determined by the biomechanics of the movement!

And never forget to hold the breath, even without a load, for this is what nature decreed should happen to stabilize the trunk and protect the lower spine! Your blood pressure will rise in proportion to the size of the load and the amount of effort that you are willing to put into the action. If you have cardiocirculatory problems, and you insist on squatting with weights, then keep your mouth open and gradually breathe out to prevent intrathoracic and intra-abdominal pressure from increasing too much – and avoid using maximal loads!

[Regarding to POSITION OF THE TORSO during squatting: I believe many people get confused by the advice to keep one’s back “straight." Dr. Siff is right, in my experience — you can’t keep your torso perpendicular to the floor without some sort of odd foot position. But you MUST keep an arch in your back. The technique I’ve always used is to keep the arch in the lower back and neck buy sort of “pushing out" the chest and abdomen and looking slightly upwards.

The belief that the spine must be straight during squats and deadlifts is another one of those confusing snippets of ill-explained training lore.]

STRAIGHT BACK?

The ‘advisers’ probably mean that the spine should not be flexed forwards or extended backwards, in some sort of hypothetical straight line. When challenged on this point, some of them state that this is their simplified way of stating that the spine should be kept in its neutral position, whatever that means in the context of a dynamic lift involving a line of action which changes all the time relative to the direction of the gravitational pull.

PATTERNS AND RHYTHMS

Some authors (e.g. Cailliett ‘Low Back Pain & Disability’) refer simplistically to a lumbar-pelvic rhythm that must be followed to ensure safe lifting (or squatting), but we have to look at the whole body as a linked system to appreciate that the actions of squatting and lifting involve many more actions than those of the pelvis and lumbar spine alone. However, these authors are correct in identifying that there is a characteristic rhythm or timed pattern of anatomical (kinesiological) action for the optimal and safe execution of every exercise.

In the case of the squat, there is a definite rhythm of how the different joints (ankle, knee, hip, spine) become involved in producing an efficient and safe movement. This rhythm or timed pattern is really like an exquisitely orchestrated symphony conducted under automatic and voluntary control of our brain and nervous system. Every instructor or coach has to conduct a client’s orchestra to produce individualized nervous programs in the brain so that the muscles will obey the commands to execute an exemplary squat.

POSTURE AND NEUTRALITY

One must maintain a definite lumbar curve during the squat, but this is where some authorities differ. Some consider that this constitutes lumbar hypertension and can damage the spine, so they talk about neutral posture, even though neutrality is defined to apply under static standing upright.

As soon as you lie down or tilt the spine relative to gravity, then we can attempt to maintain the three natural mobile curvatures of the spine (cervical, thoracic and lumbar), but this necessitates increasing muscle tension and changes in other joint angles to approach this standard of ‘neutrality’. So, the appearance of neutrality is quite different under different actions. Even though the spine looks like it is structurally in the same relative shape, functionally the muscles, ligaments and other tissues are in radically different states of tension and operation. In other words, the concept of neutrality (like all the ideas about pelvic tilt) is not at all as clear-cut as out medical and physiotherapeutic colleagues would have us believe.

APPROPRIATE LUMBAR POSITIONING

To resolve the issue of lumbar ‘hyperextension’ during squatting or lifting, we must analyze what stabilizes the spine under different conditions. The muscles act as dynamic or static active stabilizers (since they can contract), while the ligaments act as passive stabilizers (they cannot contract). In maintaining the three natural spinal curvatures, it is pleasing to know that both the muscles and the ligaments (and other tissues such as the fascia, as well as the pressurised trunk) all cooperate to stabilize the spine.

However, we cannot say that the loading is distributed equally between muscles (e.g. erector spinae) and ligaments. This ratio is determined by one’s way of squatting. So, if one tightens the erector muscles as much as possible, this may cause some of the ligaments to slacken, thereby placing a greater load on the muscles. If one avoids tensing the erector muscles too much or allows the lumbar spine to arch forwards, then the ligaments may bear much greater stress and the muscles tend to decrease their strength output.

DYNAMIC STABILIZATION

It happens that there is an optimal balance between these two undesirable extremes which allows the contribution by muscles and ligaments to dynamically adjust to different phases of the squat from the starting to the end position. The trainee or lifter learns this optimal dynamic balance by tons of experience, some of which is by the bitter way of making painful or damaging errors.

There is not one precise static position of the spine or hips, though there is a typical ratio at each set of joint angle (knees, hips, spine, neck etc.). The ratios change over the range of movement and one learns to develop great proprioceptive skills to enable you to adjust rapidly and automatically.

So, we can now appreciate how inadequate it is in the overall picture to learn by squatting onto a seat or in a part range movement from which we are told never to deviate, because one must use a specific single type of pelvic tilt, lumbar angle of concavity, knee angle and so forth.

OBVIOUS ADVICE

We can, of course, make cautionary statements about avoiding actions which have been seen to have caused serious injuries during squats and all exercises, for that matter – such as rounding the lower back and twisting simultaneously, bouncing vigorously in an uncontrolled fashion on totally relaxed, using a weight which is too heavy to maintain appropriate technique, bouncing the buttocks off a seat while using a significant load or accelerating rapidly and squatting when one is fatigued, sore or injured. Such advice is wise and advisable. But first and foremost are the rules that perfection of technique and intuitive sensitivity to any changes will go a long way to preventing injury and ensuring progress.

Dr. Mel C. Siff Denver, USA 1995